- Home

- Susan Rice

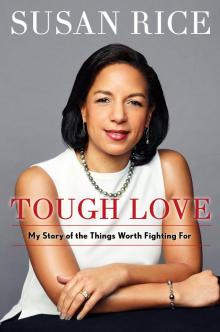

Tough Love Page 4

Tough Love Read online

Page 4

Like many New England colleges and universities in the post–Civil War era, Bowdoin admitted very few African Americans. While known as the college that graduated one of the first black students, John Brown Russwurm in 1826, Bowdoin’s record on integration was otherwise poor. It did not have another black graduate until 1910.

To raise additional funds to send his sons to Bowdoin College, my grandfather rented out the other apartment in his house and remortgaged their residence. After each of my four uncles graduated from Portland High School, all went to Bowdoin, working part-time jobs to help pay their tuition and support the education of their younger siblings. My grandfather, reputedly the first man to have four sons attend Bowdoin, was proud when years later Bowdoin’s Class of 1912 made him an honorary member—the year that he would have graduated, had he attended college.

My uncles all lived up to their parents’ expectations, if sometimes fitfully and dramatically. Each achieved professional success—two became doctors, one an optometrist, and the other rose up through the academy to become a university president.

My uncle Leon, the firstborn, was dominating and charismatic. After a stellar record at Portland High School as an Eagle Scout, concert master, and chess champion, he graduated Phi Beta Kappa from Bowdoin in 1935, as only its ninth black graduate. He went on to Howard University Medical School, having been denied admission to Harvard because, he was told, there was no other black man with whom he could room.

A rebel against his parents’ almost puritanical child-rearing, Leon got away with misdeeds that only a cherished firstborn son could. After my grandfather took out a loan to fund his medical school tuition, Leon blew his entire stipend gambling with friends. With no other option, my grandfather—furious, embarrassed, but determined—pleaded for and was granted another loan on the basis of his character and credit. My favorite part of this story is that Leon’s gambling buddy, who had taken his tuition money, confessed on his deathbed to cheating my uncle that night and over the years.

During and after World War II, Leon served at the Tuskegee Veterans Hospital, where he established a reputation for being outspoken about “Southern prejudicial practices.” He railed against the Veterans Administration and successfully resisted their efforts to send him to Waco, Texas, to work in what Leon called “mixed, Jim Crow facilities as flunkies for cracker heads.” Leon later established a highly regarded family medical practice in Detroit with his wife, Val, a nurse. A committed Republican who was deeply involved in the Detroit NAACP, Leon believed he could best serve his community by charging his patients, mostly black factory workers, the same fees in the 1990s, when he retired, as he had when he started practicing in the 1950s.

My second uncle, Audley, left Bowdoin after two years, completed his degree in optometry at Columbia University, practiced in New York for thirty years, and married but had no children. I remember him from my early childhood as a sweet, selfless man whom all the Dicksons adored. A longtime smoker, he died of throat cancer in 1969, after enduring a permanent tracheotomy for years. Deemed the glue that kept the family close, his loss was an enormous blow to his parents and siblings.

By his own description, my third uncle, David—the family historian and a kind, humble man—was a sickly, socially awkward child who buried himself in history and literature library books. An accomplished debater and valedictorian at Portland High School, Uncle David was a phenomenon at Bowdoin. Only the second student ever to receive straight As in every subject over four years, he was honored as junior Phi Beta Kappa, summa cum laude, and valedictorian of the Class of 1941. His record of achievement aside, David felt ostracized at Bowdoin. As a black man, he and the few Jewish students were barred from joining fraternities and, as he wrote years later, the “psychological impact of that kind of arbitrary, completely undemocratic, un-Christian, and anti-Semitic exclusion was overpowering.”

After obtaining his PhD in English literature from Harvard and becoming commanding officer of the medical unit of the 2143rd Army Air Field Base Unit at Tuskegee, Alabama, Uncle David decided to pursue a career in academia—a struggle, it turned out, at a time when only a handful of black professors taught at white institutions. When his own alma maters, Bowdoin and Harvard, refused to hire him, David turned to a favorite professor, who helped him secure an appointment as assistant professor of English at Michigan State University. David’s long career took him to Washington, D.C., Long Island, and Montclair State University in New Jersey, where he was president from 1973 to 1984. I enjoyed getting to know him well, along with his sweet wife, Vera, and my three cousins, starting when they lived near to us in Washington.

Though I never met my uncle Frederick, the baby boy of the family, I reveled in the legendary stories about him. Fun-loving, exceptionally handsome, and a playboy fancied by all, Freddy was a three-letter varsity athlete and football star at Bowdoin. After serving in World War II, Freddy earned his medical degree at the University of Rochester and returned to military service in Japan during the Korean War. Back stateside, Freddy joined his brother Leon’s medical practice in Detroit. Tragically, he died of a cerebral aneurysm on Thanksgiving night in 1957, at just thirty-five.

Devastated by the premature loss of their youngest son, my grandparents sought to make the best use of Uncle Freddy’s $10,000 GI life insurance payout, a massive sum for a family that had never earned more than $5,000 a year. Instead of keeping the money, they gave it to Bowdoin as an annuity in Freddy’s honor, which after my grandfather’s death became the Mary M. and David A. Dickson Scholarship Fund to assist low-income students from Maine to attend the college. The fund has multiplied over the years and still thrives as testament to my grandparents’ commitment to education and their love of Bowdoin.

My mother, Lois Ann—a surprise, long-awaited girl—arrived in the wake of her highly accomplished brothers. Back then, my forty-four-year-old grandmother had good reason to fear she might not survive another pregnancy or, if she did, that her child would be developmentally disabled. However, my mom emerged healthy and hardy, to the delight of her parents and her four older brothers. Eleven years junior to her youngest brother, Lois grew up effectively an only child. Although she was “the little princess” of the family, Lois was not to be outdone by her siblings.

By the time my mother was born in 1933, my grandparents were more established financially, and Lois enjoyed nice clothing and private piano lessons—without the need to work, as her brothers had during their school years. Still, her parents’ ambitions for their daughter were no less than for their sons, and Mom felt the same responsibility, if not pressure, to excel—even at a time when few women went to college, much less on to professional accomplishment.

By every measure, Lois set the bar exceedingly high for those, like me, who came behind her. She was the star of the Portland High School Class of 1950: valedictorian, student council president, a concert pianist, and a champion debater. Her accounts of those days were also filled with memories of an active social life, dates with good-looking college guys, and lasting friendships. As her daughter, I was always awed by how easily my mother connected to others. She had a real knack for adopting strangers and making them feel as if they belonged.

Lois and her brothers grew up socializing mainly with white kids, because blacks in Portland were so few. Still, my grandmother, despite her own mixed background, drew the line for my uncles at interracial dating. Mary viewed America as less racially tolerant than Jamaica and thought interracial marriage would ruin her sons. She told her Dickson boys to stay away from white girls, assuring them, as Uncle David recalled, that they would eventually find “Colored girls of beauty, charm and intelligence, in shades like the rainbow or a garden of beauty.” Mary was highly judgmental about my uncles’ choices in women, undermining those relationships she thought unworthy and pressuring each boy to marry either Jamaican women or light-skinned black Americans. And while I don’t recall her saying so in my presence, I suspect Grandma was unimpressed with my mother’s ch

oice of my mahogany-brown father.

When it came time for Lois to attend college in 1950, my grandparents were flummoxed. My grandfather dreamt he could persuade Bowdoin to take women, or at least one, but Bowdoin would not accept women until 1971. Her brother, my uncle David, ultimately saved the day, recommending Radcliffe College in Cambridge, Massachusetts. It wasn’t Bowdoin, but it was conjoined with Harvard, where David had received his doctorate, and thus would suffice.

My mom’s college plans were jeopardized by a catastrophe that struck in September 1948 during the start of her junior year in high school. “That was the time,” she told me over the years, “that Grandpa fell down the elevator shaft at the music store.” He broke his back and shattered his feet. As a kid, I used to wonder how Grandpa could have failed to notice the elevator was missing. Then, one day as an adult, it hit me—as a janitor, he must have backed into the open elevator out of habit, pulling a cart or something with him. While Grandpa was hospitalized for over nine months without a salary, my grandmother returned to work as a maid to help compensate for their losses.

Soon, the family’s modest savings for Lois’s college tuition were exhausted. Number one in her class at Portland High, my mother was entitled to the State of Maine Radcliffe Club Scholarship; but it was denied to her by the chair of the selection committee. This white woman explained to my mother that the scholarship recipient was expected to return to Maine and “move in proper circles” where she might raise funds for Radcliffe. As a Negro, she claimed, my mother could not meet those expectations. Furious and offended, Mom was determined to obtain support. Fortunately, her high school principal and debate coach shared her outrage. They appealed to Radcliffe directly, which awarded Lois a $500 scholarship, $200 more than she would have garnered from the state fund. Mom also received $400 in supplementary financing from the National Scholarship Service and Fund for Negro Students (NSSFNS) for her first year and $300 for her second year. Never forgetting the value of this crucial support, Mom later devoted her career to helping others receive sufficient college assistance.

At Radcliffe, Lois Dickson came into her own, refusing to acknowledge any limits on her personal or professional ambition. Despite being an African American woman in the early 1950s, she clearly was going places.

As my mother finished college, my father was completing his PhD in economics at the University of California at Berkeley and laying his future path.

Emmett Rice was a brilliant, handsome, charming, yet complicated man whose background was quite different from that of Lois Dickson. My father was born in segregated South Carolina to parents who were the children of slaves. Despite the proximate legacy of the Civil War and the backlash against Reconstruction, my paternal grandparents, and even my great-grandfather, were college-educated.

Walter Allen Simpson Rice, my great-grandfather, was born a slave in South Carolina in 1845. At the age of eighteen, following the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863, Walter joined the Union Army during the last bloody years of the Civil War, serving with the Massachusetts 55th Volunteer Regiment. With the support of his benefactor, Lieutenant Charles F. Lee, Walter Rice completed his primary education in Massachusetts. Upon his return to Laurens County, South Carolina, Walter became a Freedmen’s Bureau public school teacher and entered local politics. Shortly after being elected county clerk, however, his tenure ended in his exile from Laurens County when, as my father recounted, great-grandfather Walter faced death threats from the Ku Klux Klan and fled to New Jersey. Walter went on to obtain his divinity degree at Lincoln University in Pennsylvania and eventually became a presiding elder in the New Jersey branch of the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church.

Even more than his rare education, what impressed me most about my great-grandfather was his deep commitment to the advancement of former slaves. Rev. Walter Rice spent ten years collaborating with fellow black faith leaders in the New Brunswick area on the founding of the Manual Training and Industrial School for Colored Youth, more commonly known as the “Bordentown School.” Sometimes dubbed “the Tuskegee of the North,” the Bordentown School opened in 1886 with just eight students in a two-story frame house on West Street. Its ranks gradually filled with additional students, many of them homeless or abandoned children and some whose working parents could not find an appropriate school to house them. With limited funds to support his growing institution, but a grant of $3,000 from the state, Walter Rice was able to lease seven small buildings scattered across Bordentown.

In 1897, the school was bequeathed a highly coveted thirty-three-acre estate, which gave it a greatly expanded campus with panoramic views overlooking the Delaware River. At the same time, Bordentown began to receive sustained state support and eventually became part of the New Jersey public school system.

On our way to and from Maine, Dad would point out the exit off the New Jersey Turnpike for Bordentown, explaining to me and Johnny with pride how the school epitomized his family’s devotion to education and the socioeconomic advancement of blacks. Though we never stopped to visit the dilapidated former campus, Dad described how Bordentown eventually became a highly successful, four-hundred-acre coeducational boarding institution, which taught its approximately 450 students technical skills such as farming and cooking, as well as a full college preparatory curriculum, ranging from Latin to physics. For generations, the school produced leaders in the African American community, while welcoming such luminaries to campus as Booker T. Washington, Mary McLeod Bethune, Eleanor Roosevelt, Albert Einstein, and Duke Ellington. Ironically, Bordentown was compelled to close in 1955, after the Brown v. Board of Education decision rendered the all-black, state-supported institution legally unviable.

Great-grandfather Walter Rice died in 1899 at fifty-four years old, the father of six children by two wives. One of those children—from his first marriage—was my grandfather, Ulysses Simpson Rice, who followed his father’s path, first to teaching and later to the ministry. With a divinity degree from Lincoln University, Ulysses returned to South Carolina and married my grandmother, Sue Pearl Suber. They had four children: Ulysses Simpson Jr., (known as Suber), Gladys Clara, Pansy Victoria, and the youngest, my father, Emmett John Rice.

Born in 1885 in South Carolina, Sue Pearl, my grandmother, whom I remember as warm and dignified, was the daughter of a successful farmer and former slave, Pratt Suber. Chairman of the Laurens County Republican Party and county commissioner of education in the 1870s, Pratt was reputedly forced out of those roles by angry whites. As a public official, Pratt faced nearly constant harassment from whites who resented black gains during Reconstruction. In 1880, he was badly beaten while attending a large meeting of Republicans that was broken up by a white Democratic mob.

Two generations later, my father was born to Sue Pearl and Ulysses Rice on December 21, in either 1919 or 1920. (Various documents record his birth date differently.) Like my mother, Dad was a final child and happily unexpected. His elder sisters, Pansy and Gladys, were nine and ten and a half years older, respectively, and his brother, Suber, twelve years his senior. Emmett enjoyed a comfortable early childhood in Sumter, South Carolina, where his father was a widely liked, respected pastor and community leader. The family lived in the Mt. Pisgah AME church parsonage house, a well-appointed large clapboard. At seven, Emmett’s idyllic life was upended by the sudden death of his father. My grandfather, Rev. Ulysses S. Rice, died in November 1927, at age fifty-one, from an undiagnosed heart condition. This shocking loss of his beloved father wounded my dad, leaving him vulnerable and lacking a strong male role model.

Shortly after my grandfather’s death, my grandmother Sue Pearl lost the privilege of living at the parsonage house and faced almost immediate economic hardship. To support her family, she went back to school at age forty-two, using what savings she could muster. Having already attended Scotia Seminary, a North Carolina normal school equivalent to two years of college, Sue Pearl enrolled at Morris College in Sumter to get her bachelor’s degree in teaching. As a teach

er, Grandmother Sue Pearl became a rare working mother, in contrast to her peers who were mostly housewives. My father always told me how much he admired his mother’s determination to provide for her family and professed complete comfort with women working outside the home. (In later years, Dad supported my career every step of the way, even though he struggled to apply the same standard to my mother.)

Sue Pearl moved her family from South Carolina to New York City around 1933 to join her eldest son, Suber, and to attain higher pay and a better education for her children, particularly Emmett. Having spent his first thirteen years in South Carolina, my father subsequently moved back and forth between New York and South Carolina until he graduated from high school. For Emmett, New York held the theoretical promise of a desperately desired respite from the daily humiliations of segregation. Indeed, my father never knew a white person well until he moved north. Unfortunately, New York sorely disappointed, as Emmett found his geographic boundaries circumscribed to Harlem and the few establishments, like the neighborhood YMCA, that allowed blacks.

At seventeen, Emmett enrolled at City College of New York (CCNY), one of the few affordable colleges in the city that catered to immigrant and working-class students. An urban, all-commuter school, CCNY was impersonal; my father found his professors aloof and little to bind him to the campus. While his classes were integrated, my father recalled, “There was a great deal of prejudice. White students… didn’t have very much to do with me. I was pretty much isolated in college.… There weren’t many black students,” and those there were were “so scattered that I never had another black student in a class.”

Tough Love

Tough Love